UNIQUE AFTER-WAR MEMORIAL AT TALLY HO FARM WINKFIELD SL4 4RZ ENGLAND

UNIQUE AFTER-WAR MEMORIAL AT TALLY HO FARM WINKFIELD SL4 4RZ ENGLAND |

| Why bombees should treasure family historians | |

|

| A personal take on a night to remember | ||

|

INFORMATEERS |

IF

I HAVE A SPECIAL INTEREST in the events around

Thanksgiving Field, it's because our family had a

first-hand experience of being bombed - not by a

B17 but a Heinkel 111. IF

I HAVE A SPECIAL INTEREST in the events around

Thanksgiving Field, it's because our family had a

first-hand experience of being bombed - not by a

B17 but a Heinkel 111. And it helps explains why I see my Mum as a hidden hero for her quiet resilience during those days and throughout the war, somehow coping not only with Us but Events, too. It was a role that many women played on the Home Front in many countries - and still is. If you look around your own family, you'll be able to see many a hidden hero helping other lives have happy landings. It also throws light on the nightmares and fear of the dark in my early teens - already showing on my first day at school in August 1943. In November 1940, we were living in a nice double-fronted Victorian detached in Moseley, a residential part of the city, several miles south of the industrial heart - and about 300 metres outside the evacuation zone for children. In the house were my Mum, my sister Bunny, my brother Paul, and me. Dad was away that in Coventry - which had been hit a few nights before. His job during the war included the supply of brass for cartridges - a nice link with Thanksgiving Field. The story below is by Bunny, and shows the value of someone setting down key events. She wrote it up in in the 1990s as part of a long account of the family history. At the time of the bomb she was in her last year at King Edward's Camp Hill School. In 1941 she started studying Law at Birmingham University. Her course was interrupted when she was conscripted into the WRNS in 1943, serving as a Stoker on little boats in Plymouth and Dartmouth in Devon. She eventually completed her LLB and went off to be a barrister. But she always had a keen eye and good memory for history, as you'll see here. This section of the account starts in the late summer of 1940, just after the Battle of Britain. |

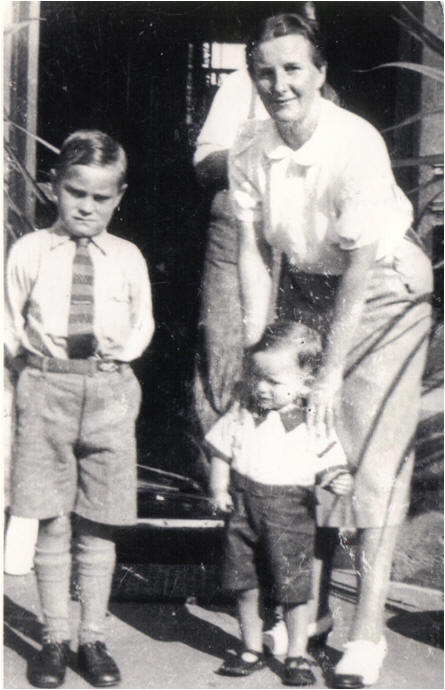

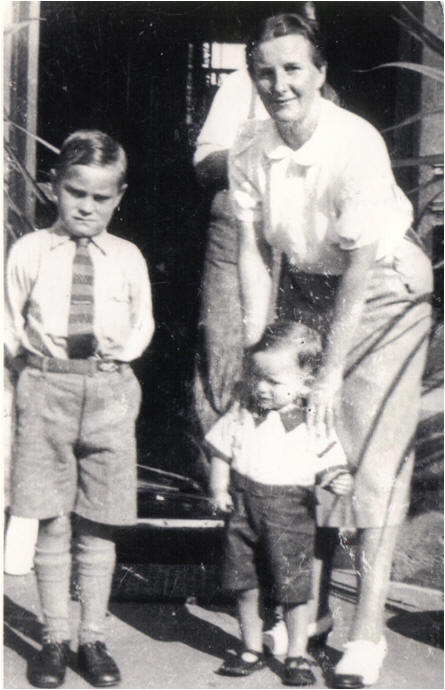

"Kingswood" 71 School, Road Birmingham 13 in October 1940 with Paul outside  ...reconfigured on 19 November 1940.  And today, on Google Streetview. Next door's chimneys have gone! |

|

|

||

| "How did you get in? I bolted the front door." | ||

The summer months dragged on and we went for

a brief weekend to Rhyl, but it was difficult to

find the way back, as all road signs had been

taken down in case of invasion by parachutists

and people were suspicious of giving directions. The summer months dragged on and we went for

a brief weekend to Rhyl, but it was difficult to

find the way back, as all road signs had been

taken down in case of invasion by parachutists

and people were suspicious of giving directions. |

||

|

The bombing raids began in the Autumn. On moonlit nights, we discovered the bombers did not come and then we went to the cinema in Kings Heath despite the blackout. The German planes were quite distinguishable by a sort of chug-chugging noise their engines made. One weekend, when my father was home from Rugby, he went up to the attic to see the fires raging the other side of the City, where they were trying to hit the munition factories, but wearing a toy tin helmet of Paul’s as protection for his head. There was one tragedy where a bomb dropped in nearby Oxford Road on to a house where a school-friend of mine from Camp Hill Grammar lived with her mother and step-brothers and sisters. They were all killed. The step-father, being an Italian, had been interned in the Isle of Man and had no idea that Birmingham was being bombed, otherwise he would have made arrangements to move the family. Then came the 19th November 1940. As the raids progressed, we had taken to sleeping down the cellar, although it had been declared not safe against bombs. We had proper beds down there, and Hugh slept in his little cot. The dampness had been dissipated by putting trays of lime down on Grandpa’s advice. On that particular night, I had washed my hair and climbed into bed by my mother’s side at about eight o’clock when the bombers would arrive. There was a great deal of gunfire as well from the guns in Swanshurst Park. Eventually, we turned out the light and fell asleep. Suddenly, we were awakened by streams of plaster falling down thickly upon us, so that the bed clothes were heavy with it and, when it finally ceased coming down, they were difficult to lift off. We were in darkness, but managed to find a candle to light. Hugh still lay in his cot, but, resting on a beam inches above it, was the gas fire from the dining-room. Had it dropped further, he would have been killed. The stairs up from the cellar were intact and we went upstairs and into the back part of the house where thing seemed normal. There was a commotion at the front as great, burly rescue men tramped in. My mother said in a bewildered voice, ‘How did you get in? I bolted the front door’. They then told us that there was no front to the house. The bomb, when it fell, had hit the front porch, exploded and blown off the front of the house so that it was open like a doll’s house. In the cloakroom at the back, the telephone had been blown off its stand and the telephone operator knew that something had happened and alerted the rescue service. In all the heavy bombing, it had taken them on a few minutes to reach us from the centre of town. We passed the rest of the night till dawn under the stairs, Hugh with a bag of biscuits all to himself which he was always to remember. The next morning we dressed in the clothes we had prepared for such an eventuality down in the cellar and my mother telephoned to tell my father the news in Rugby. He thought at first she was joking when she said we had received a direct hit, but were all safe. Had the bomb fallen directly down on to the cellar, we would not have been alive; the front porch had saved us. All that had happened was that my mother had a piece of grit in her eye and my clean hair, for weeks afterwards, was full of plaster. My father travelled up from Rugby immediately and arranged that we should go back there with him to stay in the digs with the family who looked after him until we could find somewhere to live. But Coventry had been bombed at the same time as us and thousands from Coventry had fled to Rugby and accommodation was at a premium. Again luck was with us. Someone in my father’s office knew of a Flight Lieutenant and his wife who owned a two-bedroomed bungalow in St Mark’s Avenue, Old Bilton, a village about two miles out of Rugby and, as they were moving away for one of the RAF postings, they were willing for us to have the bungalow. It was furnished, which was just as well, because only a few pieces of furniture remained from our old home, mostly from the dining-room, and they were very badly battered, literally pieces of wood in some cases. My father and mother went back to Birmingham to gather together what they could and my mother eventually found her engagement ring, shining in the rubble. At the top, where the attic had been, was the large cabin trunk we had taken on holiday with us and this contained my mother’s and father’s love-letters. My father was adamant that all Moseley was not going to read them and so climbed up, perilously, and managed to topple the trunk down with a crash. Our house was the only one which had been hit in School Road that night and my father always attributed it to his being on the Germans’ black list for having written rude letters to the German Embassy when Ribbentrop was ambassador there. But, in fact, the bomber had dropped a stick of bombs, some to the left, some to the right, lower down in Moseley and people said it was because a gun was mounted on an engine which hid under the railway bridges as the bomber came over and it had been trying to hit that.

After the bombing we went to live in Old Bilton

and then Rugby, but returned to a house in

Greenhill Road, Moseley, in 1943 - about half a

mile from the one where we'd been bombed out.

And the letters that my father had rescued? Bunny records that some time later they had a session going through together in the garden in Greenhill Road - which ended in a big argument and the letters going on a bonfire. |

My mother, Paul and me on the doorstep in October 1940  Paul in the back garden, in his tin helmet later worn by our father, perhaps goading Goering.  "YOU WERE ONLY SUPPOSED TO BLOW THE BLOODY DOOR UP" No 71 School Road after the bomb. In the bottom right hand corner is one of two bergere cane chairs, the only furniture to survive the bombing. Both are live and well and living with Matthew Gibbons in Warfield - about two miles from Thanksgiving Field!   The novel Mr Blettsworthy on Rampole Island by HG Wells - showing the hole in the spine made by what seem to be two fragments of the bomb.  My father's note onthe inside cover says: "This book contains a piece of a German bomb which demolished our house Kingswood, 71 School Road, Moseley, Birmingham on 19/11,40, in a great raid following that on Coventry the previous week. My family in the cellar had a miraculous escape: Ilma (Mum); Bun (18); Paul(7) and Hugh (2). |

|

| Afterthought: why us? | ||

|

Why was our house hit - given that it was in a

residential area several miles south of the main

industrial heart of Birmingham? Leaving aside my father's attractive Ribbentrop theory, I've come across three suggestions, and my own belief. 1. Bunny's was the gun on the train in Moseley - unlikely, because it was too specific a target, and munitions factories were the main target for the night. 2. A teacher at King Edwards School that I attended 1951-7 said that the German bomb aimers mistook the railway cutting at Moseley for one near Longbridge, near the big Austin factories. But the German bombers were using a system of radio beams to give precise navigation. However, the in the book Most Secret War, Professor RV Jones revealed that false signals were being sent out by the British to mislead the pilots 3. So a third possibility is that the bomber dropped a stick of bombs where the signals indicated but got us instead of the British Small Arms factory - a new take on Friendly Fire. 4. My own belief is that the crew did what was quite common during night raids using visual aiming equipment in WW2 - dropped the bombs and got the hell out of it. This was called Creepback. It was natural enough. Harassed by searchlights, anti-aircraft guns, night-fighters, and having difficulty making out the target or markers because of smoke or fires, crews might flinch a little - and a tiny delay in the air could means big distance differences on the ground. Not only the Luftwaffe was susceptible. Wikipedia says: "The RAF could find no effective counter to the problem of Creepback, and eventually incorporated it into their mission planning. The initial aiming point for a bombing raid would be set on the far side of the target as the bomber stream approached, allowing the bombing pattern to 'creep back' across the target, which was usually an industrial or residential district of a city.

"Creepback may not have been so

pronounced during American day bombing raids,

because the large, tightly-packed American

bomber formations dropped their bombs together

when the formation leader's aircraft bombed. In

the British bomber stream tactic, by contrast,

each aircraft bombed independently while flying

at a set height and course. |

|

|

| On the ground in Schweinfurt | ||

|

Beneath the factory where he worked, the 15-year-old lay huddled and frightened in a storage tank.

At the end of the half-hour raid, during which

more than 3,000 bombs were dropped on the

industrial city of 50,000 residents, he ran

through the burning wreckage of the building. Unlike many of his co-workers, he got out alive. Gerhard Bellosa, also then 15, had been conscripted as a “flak helfer,” one of about 2,500 German students ordered to man anti-aircraft batteries around Schweinfurt. Two months earlier, Bellosa had been at home with his mother when a 500-pound American bomb had levelled their house and destroyed all their possessions.

They had survived in a bunker underneath.

They hid in the bunker. The bombs took a fearful toll in Schweinfurt, killing 276 Germans, mostly civilians.

“Black Thursday was a fatal day, for you as well

as for our town,” Gudrun Grieser, the lord mayor

of Schweinfurt, told Americans at the ceremony,

“but now it is your home, too.” |

PASTOR DIETER SCHORN He too experienced the bombing. His father Henry was pastor

at

Lohr in Rothenburg. In 1942, the father was

transferred to the church of St. Johannis in

Schweinfurt, and the family followed in 1943,

"in time for the first bombing," says Dieter

referring to 17 August. Dieter is the person who

kindly arranged for soil

|

|

|

INFORMATEERS |

||